Katrina Plus Five

We're making that request again. Stay tuned for more.

Love

Mindy and Paul

Devastation - Transformation - Jubilation A story of St. Paul's Episcopal Church in the Lakeview area of New Orleans, LA after Hurricane Katrina

Fr. Will Hood greets Carl Knirk at St. Paul's

Sunday, January 28, 20007

Debbie Waldman: "We had three generations of stuff in here."

Debbie Waldmann stands outside her flood-ruined home in New Orleans’ Lakeview neighborhood, looking at the hole in the ground where a huge water oak tree used to stand.

Time stood still in the kitchen August 29, 2005

Bud and Debbie have weekends to work on any salvaging they might want to do. Before the storm, he worked for state hospital in New Orleans as a psychologist. Now, he’s working in Baton Rouge, 80 miles away, getting home when he can.

Stacey Hayden: "I had to laugh."

"Come on in," says Stacey Hayden, as she searches for the keys to the back door of the light blue stucco she used to call home.

Like most New Orleans residents who fled Hurricane Katrina last August, Stacey and her family thought they were evacuating for a few days. When the Haydens finally came back in December, they found most of what they owned had been destroyed when water from the 17th Street Canal breach flooded their Lakeview neighborhood.

"We lost our home, we lost our business, we lost our church, we lost our school, you’ve heard the story," says Stacey, who shared the modest two-story with her son, Robert, a mop-topped first-grader, and husband Rusty.

Gingerly walking over warped floors and stepping around overturned furniture and broken mementos, she points to a few sheets of Monopoly money about six feet up on the living room wall. The floodwaters that settled in the house for several weeks carried it up and left it there.

"When I first came in and saw it, I had to laugh," says Stacey, a St. Paul’s Vestry member.

But they barely had time to assess the hurricane and flood damage before the house was struck by a tornado in February that blew portions of their neighbor’s roof into their bathroom and Robert’s bedroom. Then, in early April, looters came, rifled through plastic bags of clothes she was trying to save, and walked out with a small window air conditioner that had somehow managed to escape the damage.

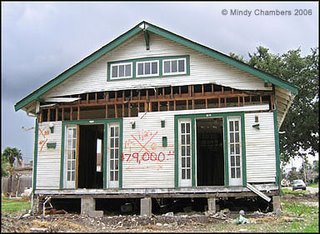

The Hayden home on Canal Blvd. bears familiar Katrina marks

Rusty only recently was able to re-open the family’s lumber business. Robert is back in school at St. Paul’s temporary location. Stacey helps Rusty with the business, sometimes takes care of other parishioners’ children, and continues to try to salvage what she can from the home while they rent a place in nearby Metairie.

Stacey shrugs as she shares their story. Tears have been replaced with humor and determination to rebuild not only her home, which will be bulldozed by Rusty, but St. Paul’s church and school and her neighborhood.

"I saved a lot of kitchen stuff – I like to focus on how much I saved."

Mindy interviews second graders at St. Paul's School in April

People who know of our travels ask, invariably, curiously and kindly: "What was it like? Was it horrible? What are the people doing? Is it back to normal? What do people need? Why are they staying there?"

It is hard to avoid answering these questions with cliches, such as "It was life-changing," although it was. I often find myself pointing to imaginary eight-foot marks (the level at which the water settled in many places in New Orleans) on walls and tend to babble in a not-so-great attempt to respond to what people want to know about the devastation. Truth is, and I mean no put-down by this, no matter how I try to answer these questions, you simply can’t understand what happened and what is happening in New Orleans unless you have been on the ground.

What was it like?

Do I describe the miles of dark, blown-out, uninhabited houses we saw on a late Friday night when we first drove through the Lakeview neighborhood, where 8,000 homes were lost? Or the spray-painted house numbering system used by National Guard units to show how many bodies and deceased pets they found during their searches?

Or do I describe the folks who have the spiritual backbone of faith that it will take to scrape away the paint (although not the memories of it) and rebuild and discover new ways of doing things in New Orleans? Do I talk about the tragedy of lives blown apart? Or do I talk about the loving hospitality offered and the life-long friendships made while we were there?

Many want to know about the stories they hear about the black vs. white, poor vs. not-so-poor in the city. I’m no help there. I can’t analyze or discuss with any kind of expertise the centuries old racial, social and economic divides in New Orleans. What I can say is that people all over the city are in need.

Was it horrible?

I think this question has two parts: Was it horrible for the people of New Orleans? Was the damage we saw horrible?

Yes and yes.

I find myself trying to explain what happened in New Orleans like this: People fleeing Hurricane Katrina thought they were leaving the city for three or so days. The hurricane passed, but the water from the levee failures filled up most of the city like a giant bathtub. Folks landed in places across the country. Those who came back, some as long as five or six months later, found the interiors of their homes looked as if a washing machine full of their belongings had been subject to a really long wash and rinse cycle that didn’t spin.

In Lakeview, a mostly white, middle class neighborhood where we spent our time, those who are choosing to stay, for the most part, will bulldoze and rebuild. I know that is not the case in the Ninth Ward, a mostly black and low-income neighborhood that we saw only briefly. Much is being written about the disparities between the two; again, I don’t pretend to analyze or judge any of this.

In both places, many people went back to their houses, took a peek inside, closed what was left of their doors and walked away. It was too painful to try to reclaim whatever was left. They won’t be back. Others chose to not return at all. House-for-sale signs outnumber FEMA trailers just about everywhere.

What are the people doing?

Surviving. Making plans for the future as best they can. Trying to make mortgage payments on homes they can’t live in and payments on cars they can’t drive. Fighting with insurance companies. Finding humor where they can. Taking their kids to school. Trying to find jobs and

People say: "I can’t imagine that" I respond by saying, "No, you can’t."

reopen businesses. Getting out of bed every morning and putting put one foot on the floor, and then another, and then managing to get on with the day. If you are in New Orleans to stay, there’s not much more to do than that. Folks don’t try to answer the question "where do I start?" They just start.

Is it back to normal?

No. Imagine life in a neighborhood with no schools, no day-cares, no dry cleaners, grocery stores, doctors or dentists. A gallon of milk or a pair of sneakers or a six-pack can’t be found at the nearby convenience store or strip mall – those stores just aren’t nearby anymore.

I believe that more troubling than the loss of stuff was the loss of routine, the day-to-day things most of us don’t have to plan for, or even really think much about. Two-thirds of the city’s population still hasn’t come back, and there’s speculation that many never will. The effects of this on neighborhoods, businesses and yes, that blessed routine, are profound. When people say: "I can’t imagine that" I respond by saying, "No, you can’t."

The things that do speak of normalcy are precious. Some folks are beginning to re-landscape – occasional lawns are popping up, and gardens are being re-planted. Birds and squirrels are returning after a several-month absence, along with the housecats that stalk them. At the home of our New Orleans hosts, Phil and Natalie James, sparrows fed chirpy new babies nesting in a bright red birdhouse.

The James were among the blessed – their home was on high ground and did not flood. But like everyone else, they have a harrowing story about having to evacuate by boat, move to another state and worry about what was going on in their city until they could return weeks later. Their neighborhood now is much like the suburbia many of us are used to, with a few exceptions: holes where large trees used to be, FEMA trailers nearby, the occasional stinky refrigerator waiting on the curb for pickup, and the sound of relentless pile-driving that’s shoring up the levee nearby.

What do people need (or not)?

They don’t need or want to be known as victims. These folks are survivors. They don’t need boxes of cast-off clothing that is ripped and full of holes. They don’t need pity or understanding nods or "I’m sorrys".

What they seem to need most of all is simply to talk to people who are willing to just listen – it helps them process what has happened. They need to know that after nine months, we haven’t indulged our incredibly short attention spans and forgotten them. They need to know that someone still cares about them. They need to know that we are praying for them. They need to know we don’t second-guess their decisions to rebuild.

Why are they staying there?

This is easy. New Orleans is home – pure and simple. No matter what neighborhood they live in, or used to, these folks are New Orleanians. Their city and their culture: their music, their food, their Mardi Gras celebrations, their history and their heritage keep them there. I find myself wondering what it would be like if I’d never moved more than a block or two away of where I grew up, instead of moving across the country. Would I feel the same way if my city was destroyed? Would I feel angry at storms and flooding and tornadoes and looters? Would I share the same resolve these folks do? Or would I, seeking some kind of safety, just move on?

Mardi Gras doll found at St. Paul's during a Saturday work party

As we made our decision to go to New Orleans, I somewhat self-righteously declared (and I am prone to these sorts of declarations) that this would be a Holy Week pilgrimage. In my mind, that meant that no matter what obstacles Paul and I faced along the way, we weren’t allowed to complain. After all, pilgrimages are all about discovery, not frustration.