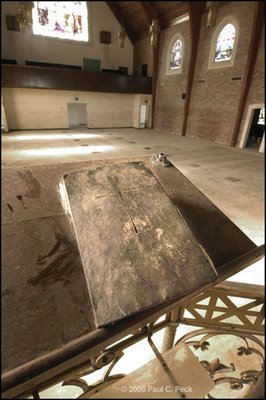

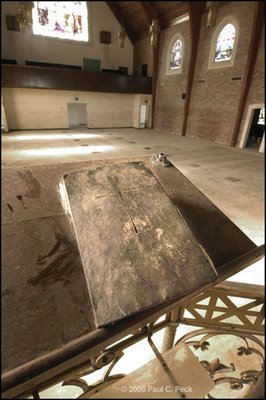

A moldy Prayer Book sits in the stripped out nave

Tucked into a straw basket dwarfed by a huge white marble altar at the front of a sanctuary stripped to concrete, brick and studs, a few words printed on slip of paper knit the hopes of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in New Orleans into a simple prayer.

"Please God, we want to worship you here in this house Easter morning. Enable Will, enable us, soften the hearts of those who say no way, to greet your risen son as we have for so many years in this very place and to welcome our neighbors in lifting our joy and praise to you. Thy will be done."

Easter Day 2006 comes just over seven months after August 29, when Hurricane Katrina slammed into the Gulf Coast. In some places where the storm hit, her wind-driven water washed in, and then out.

In New Orleans, the storm passed, but the water didn’t. It accumulated in Lake Ponchatrain, overwhelmed, and then breached, the city’s canal system in four places. The 17th Street Canal rupture flooded St. Paul’s, its school, and nearly 8,000 homes in the Lakeview neighborhood, including those of nearly all of the church’s members.

St. Paul's under 8 feet of water, early September 2005

"Water is a really, really powerful thing," says Debbie Waldmann, a first-grade teacher at St. Paul’s pre-K through eighth grade school. She, husband Bud and daughter Sarah lost their home to the flood waters.

They are among the parishioners who now face the challenge of rebuilding their lives, their homes, and the St. Paul’s church building and school. This journey will not be an easy one, but begins with a courage grounded in the faith that God will guide St. Paul’s in new directions and into new ministries. In the Diocese of Olympia, we share this journey through the We Will Stand with You project, a partnership with St. Paul’s.

Life in St. Pauls’ Lakeview neighborhood, like all of New Orleans, is defined like this: "before Katrina" and "after Katrina". Before Katrina, folks there lived pretty much like you and I. They got up, took their kids to school, went to work, went to church, went shopping. Now, day cares, doctors and dry cleaners, gas stations and grocery stores, restaurants and retailers, all those things that used to be on the way home, are miles away.

Pews left in a jumble; all were ruined by the flood

Before Katrina, the people of St. Paul’s had a big nave and sanctuary where they worshipped (it filled up with 11 feet of water, which dropped to eight feet, and then hung around for three weeks). After Katrina, the congregation moved its worship services to a temporary space; its number was diminished by nearly two-thirds (average Sunday attendance is now 100 or so.

Before Katrina, the school on the grounds served about 300 kids and had a brand new gym. After Katrina, the school moved to a temporary location with less than half of its students; the gym is now filled with relief supplies.

Water still fills the spaces between the double-paned windows on the ground floor of the school. Vestments and, furniture, prayer books and hymnals are a memory; water-soaked, they were left by the curb to be picked up and added to a debris pile. Some things were recovered, like the chalice and paten, and offering plate. "Every day, we found another piece," said Natalie James, who has called St. Paul’s her church home since she was a child.

James shares the congregation’s determination to rebuild. The building has been gutted, and will be treated for mildew before reconstruction starts. Starting with a blank slate means they can plan office space, a library, classrooms, a vesting room, etc. and no longer have to cram into whatever space is available.

Roland Wiltz, the parish’s business manager; junior warden Margaret Kirn who chairs the Restoration Fund; and members of the Vestry have an ambitious plan to get the building back together and hold services there in August, with a combination of insurance, donations, some money from an endowment fund, and lots of prayer support. Plans also call for the St. Paul’s school to move back to the campus in August. Its summer camp will begin in June, as it does every year.

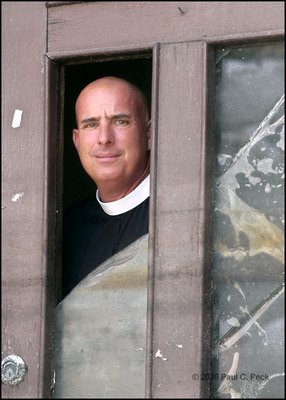

"People have chosen to stay," says Fr. Will Hood, who was called to the parish as rector in January. "They can’t think of a better place to be than St. Paul’s."

Willing hands clear debris on St. Paul's campus

Work parties of parishioners and crews of professionals are on site regularly. On a recent Saturday, they were tidying the school’s upstairs classrooms, which didn’t flood. Pews are coming from St. Paul’s in Indianapolis; new Prayer Books have been sent from a parish in Montana. Much more will be needed; and with much of its congregation scattered, or simply gone, St. Paul’s will have to rely on help from others to meet its short- and long-term needs.

St. Paul’s journey "is not about recovery, but about discovery,’ says Hood, who speaks of rebirth throughout St. Paul’s Holy Week journey from Palm Sunday to Easter.

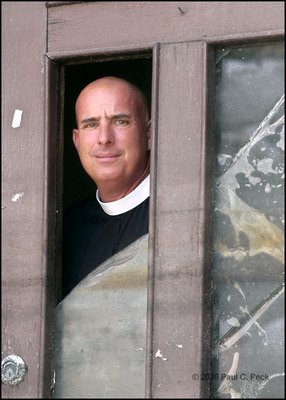

Fr. Will Hood: "Will you journey with me?"

On Palm Sunday, Hood reminds the congregation of the question Jesus asked the apostles: "Will you journey with me? Will you love me and be with me on the dark road … to the cross … and to the resurrection."

And as the resurrection is celebrated on Easter Sunday in New Orleans, more than 230 people, the most since the flood, end this year’s Lenten journey, coming together to hug, to cry, to acknowledge death, and to celebrate Christ, who has risen.

"Jesus really died – do you understand that? Oil and herbs could not gloss over it. There was a stench. It was death ... life (for the apostles) as they knew it had forever changed when their Lord and savior died. They scattered, they hid, they shut themselves in.

"Last August, it is fair to say part of our lives died. The storms came, the levees broke … then came the stench … There’s no oil and herbs for that. The dreams, the expectations, much of life as you knew it died that day."

But, like Christ, St. Paul’s is being reborn.

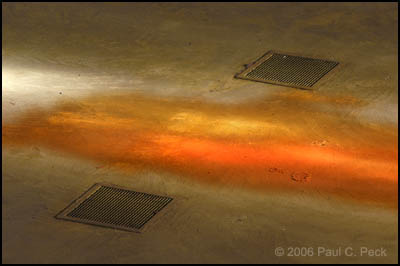

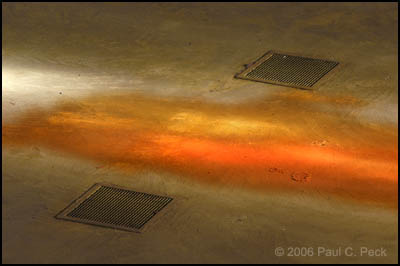

Light streams through stained glass onto bare concrete in the nave

"This is about resurrection, not resuscitation," Hood tells the congregation on Easter morning. "Resurrection admits that death happens. It looks death in the face. It is new life. It is something God does, not you and I.

"It is a new story, a new way and a new life. It’s waiting and watching and listening. It’s resurrection … flowers bloom, the heart beats, and there is new life. Amen."